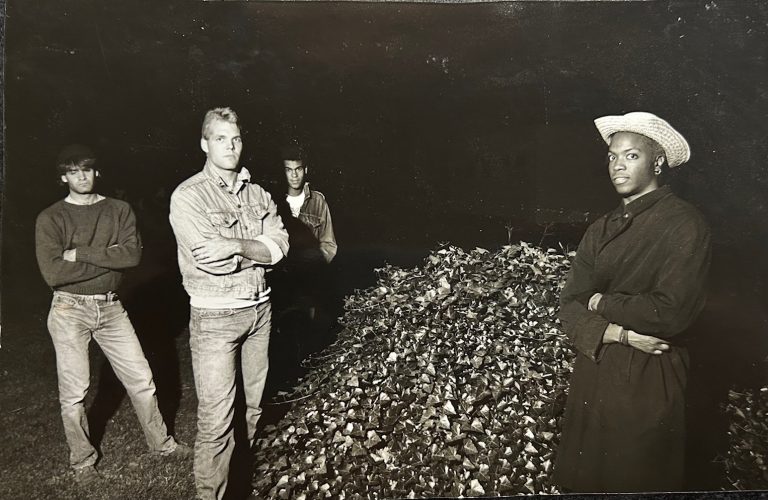

Whipping Boy revisits ‘Muru Muru’ with the remastered version titled ‘Dysillusion‘. This release, set for September 5th by Blackhouse Records, features a return of Eugene S. Robinson as our guest. When interviewing Eugene S. Robinson, one can always expect an interesting and enlightening discussion. However, this time we were treated to even more. This conversation serves as an essential education in punk rock and hardcore from someone who has lived and breathed it firsthand on the frontlines. We hope you enjoy this fascinating discussion with a true visionary.

How are you doing? Are you excited about this release?

“I’m super excited about it. And people need to understand that the fact that it’s been reissued is kind of a product of our total and complete insanity. We spent more on the remix than it’s logistically possible for us to make back on it. Now think about that for a second. It wasn’t a big hit when it came out, but it bugged us so much that it sounded so bad that we finally said, fuck this. We’re going to spend a bunch of money and make it sound the way it should sound, and let’s see if somebody puts it out. Blackhouse stepped out to put it out. But there is no way for them to sell enough of these to pay us back. They talk about labour of love. This was purely because we love the record so much. Now that I had the money to spend, I just couldn’t let it go. I absolutely could not. Steve and I talked about it for a long time and finally pulled the trigger and did it.”

A lot of people know you from your work with Oxbow and Buñuel, but Whipping Boy was your first band back in 1981. Can you take me back to that time? What was Eugene Robinson like in 1981?

“Yeah, well, if you read the memoir that I just put out on Feral House, it’ll be quite boring to you, what I’m about to say, but if you haven’t read the memoir…

My first actual band was this band called Alan the X’s in 1980, a band I played sax in and not very well either. We did six shows and then that kind of frittered out, but I had already been bitten by the bug and spent that summer doing a couple of things. Working for the New York City Department of Parks. It was my job to cover for two guys who never came to work. So that was it. I sat in an office and made a lot of money for myself, but I had an active mind, and I decided I was going to do something. And that summer, I put together a plan to both start a band and start a magazine. I started the magazine, The Birth Of Tragedy, there, I was influenced by Richard Kern, who, unbeknownst to me, was the guy who was publishing, he called it the Addict Series. So there was the Valium Addict, the Heroin Addict, the Cocaine Addict, and I found one in the subway. I looked at it, I went, That looks cool, I’ll just get it somewhere else. I got two blocks away from the subway, I think, I’ll never find that anywhere else. I doubled back to the subway to get it. It turned out it was Richard Curran with whom I later became friends. He took some photos for the second issue.

So, it was really kind of a flip-out. But that summer I came back to California, I’m gonna start a band and here’s the first issue of the magazine. They’re gonna go hand in hand together. I remember driving around on a moped in California. I just could have let the East Coast go. I had a leather jacket on and a ski cap, and it was like 98 degrees, which is very hot in California. I saw Steve Ballinger walking along, and I had known him already from the weight room, but I’d never spoken with him. Somebody had told me, I think he plays guitar, and I just fucking made a U-turn, grabbed him and said, “Hey, listen, you Steve?” He goes, “Yeah.” I say, “Well, you play guitar?” He goes, “Yeah,” and I say, “I’m Eugene, we’ve got to do this band thing!” And that was the birth of Whipping Boy. It was right at the beginning of Hardcore becoming a thing, so it was a very cool time for us.”

I’m a fucking hardcore punk rock guy at base root, so I’m completely comfortable with being hated by people.

You caught the ear of Jella Biafra quite early on, and you were included in the Alternative Tentacles compilation Not So Quiet on the Western Front, which then followed up with your first album, The Sound of No Hands Clapping, a straight-up hardcore album, and you built a following with that. What prompted the stylistic U-turn, which became Muru Muru?

“Well, it wasn’t really; there were songs off of that first record, The Sound of No Hands Clapping, like Cracked Mirror. There were songs that indicated that we had aspirations. That’s it, aspirations, period. Like the idea of turning out the same record, five records in a row. That’s not happening. So closely on the heels of The Sound of No Hands Clapping, we put out Muru Muru. A lot of bands will say, well, we just became better musicians. We can’t even say that. I mean, we were absolutely, after having done a couple of really long tours, you know, hardcore, hardcore, hardcore, playing with Minor Threat, Negative Approach, just doing a lot of great shows. But then, after you do 30 of these and travel 8,000 miles around America? The straw that broke the camel’s back was my being a writer with my interest in writing. I was starting to write lyrics that didn’t sound great in a 1,2, 1,2,3,4 format, you know? So, we kind of had a song that we liked, and that song was ‘Nevermore’, and I completely dug it because I just started getting into The Birthday Party in 1981, so it was a whole lot of different things that we figured out. We figured everybody was doing what we were doing, and it turns out that was not the case.

Like everybody did, we did what we were doing, and Scratch Acid ceased being Scratch Acid and then formed Jesus Lizard. Everybody kind of went post-punk, right? The people who have been hardcore, some of them had gone post-punk, and that made sense. And then the other half just stayed doing Hardcore. Of those who stayed, the only ones worth a damn that, for my money, right now are Agnostic Front and then the Cro-Mags. You know, Greg Ginn has reformed Black Flag, but I mean, this is to the laughter of onlookers, whatever, man. It’s cool that you did that shit in 1975. Not so cool that you did it in 2025, but who am I to judge? He was always nice to me, and I have no beef with the guy. But that’s kind of what happened.

The record, I mean, literally, probably, 175 people bought the record. You need to know, we printed a lot more than 175. It was a massive failure, but it didn’t stop us from loving it. You know, we really wished people had the minds that were where our minds were when we did it. I keep it real, none of this should have been foreign to people because during that time period, we were playing shows with the people who ended up being significantly involved in post-punk. We were playing shows with Husker Du, we were playing shows with non-standard people, James Blood, The Minute Men, people were doing stuff that was outside the box. So, it shouldn’t have been a surprise, but you know, Maximum Rock And Roll (magazine) really reached a lot of people, and that’s all a lot of people knew about it. Muru Muru was a big surprise for them. Now, from the vantage point of 35 years of Oxbow, Buñuel, and these other bands and projects I’ve done, it doesn’t seem so strange at all. It seems like a nice addition, which is why it makes sense to do it now versus never.”

You recorded the album with Klaus Floride from Dead Kennedys, and from what I’ve read, it was like the ambition didn’t match the technical chops in the production, and you didn’t end up with the sound you wanted?

“He played on it, too. He’s playing guitar on Junkman, and he did a wonderful job with that, but you know, I mean, the signs were there that we didn’t know what the hell was going on. I think either Klaus or the engineer had to explain the difference to Steve between a speaker cable and a guitar cable. We had gone into a guy’s dorm room to record the cut Human Farm. Kevin McClain had an 8-track set up in his dorm room in college, so that’s what we did. Then the second time we were in the studio was with Tom Mallon, who used to be Chris Isaac’s drummer, and was also in Negative Trend for a period of time. He was the guy who produced and engineered The Sound of No Hands Clapping, which is why that record sounds so great.

It was me who decided that Klaus is kind of how I got all up involved in those because I had met his wife at the Mud Club in New York, and she says, “you go to California, you gotta look these people up, and you gotta do two things. Well, you’re gonna do them anyway.” I go, “What two things?” She goes, “You’re gonna get your ear pierced and you’re gonna get tattoos.” But I’d already got tattoos in New York, which was illegal then. I did get my ear pierced in California, but I showed up, and I thought that I had confused Biafra with Klaus. It turns out the very first Whipping Boy show ever was with Circle Jerks and the Effigies, and Klaus and Aaron Pellegro were in the audience, and we were not scheduled to play that show. We were just all at the show, and we went to the promoters, “Hey man, our whole band is here. Can we play three songs before The Circle Jerks go on?” It’s completely crazy, right? But we figured, fuck, we’re all here. Steve, the guitar player and the co-founder of the band, is about six feet seven, about 280 pounds. I think they looked at us and figured, it’s just easier to let them play.

So The Circle Jerks, Keith Morris, we asked him and he goes like,” We don’t give a shit but you can’t use our equipment,” so then we went to The Effigies and The Effigies were like” yeah you can use our equipment.” and so when they say, “Next up from LA, The Circle Jerks!” and we walk out. That was great. We got a great San Francisco welcome with a fusillade of spit bottles and cans thrown at us, which we loved. We played three songs and got the fuck out. And Klaus came up and introduced himself after that. And that was the beginning of it. He worked on a couple of Whipping Boy records, actually. Studios were new to us then and apparently, sort of new to him too, I mean, based on the difference between what he did and what Chiccarelli could fix.”

When I listen to that album, it is so ahead of its time. On Nevermore, I can hear the influence of David Yow later on in Jesus Lizard. Of course, he was in Scratch Acid then and that sort of stuff. I can hear Minutemen in there. I can hear where Husker Du eventually went in there as well. It seemed like Hardcore was branching off, but it branched off later on. I think you were so ahead of the curve

“Yeah, it branched off in weird ways. Oxbow put out eight records, and every record I had to struggle to find a label. I remember at one point I had contacted Tony from Fat Wreck Chords. He said, Yeah, this record’s great, but it’s not punk enough. I just didn’t know what he had meant. Then, like, within eight months of him telling me that, The Warped Tour happened for the first time. I was like, “Oh shit, I see. Punk has become a genre, a very specific genre.”

Within that, Hardcore is also, I mean, nobody would have ever called Fat Wreck Chords a hardcore label. That had become its own genre, too, which was the Revelation Records in Huntington Beach, the hardcore label where they were putting out Ice Burn and Youth of Today. I like the idea of people with a shared sensibility doing what you’re digging on, whether it’s whatever sport, but all these teams have different personalities. I thought that you’d be allowed to do that with music or given access to something like that. But no, that wasn’t the case. Nobody was interested in genre mixing. So, you just had to do it and hope that the people who dug you as a hardcore band continued to dig you, and they didn’t! Not with Muru Muru. By the time we did Third Secret of Fatima, which was the third full-length album, we had gotten people back. Maybe we could have done a better job of selling it as, OK, these are what would have been B-sides, like Social Unrest had that song, I Love You. Like every hardcore band had the one non-standard hardcore song that showed intimations of where they would go if they weren’t trapped in. Harley Flanagan just described Hardcore as, “a shit that he took that won’t flush.” You know, he takes a lot of credit for Hardcore, which he can’t really, but he can take a lot of credit for New York Hardcore. So, I think that’s specifically what he’s talking about. Which I thought was a very funny way to put it.”

On this new version of Muru Muru, you’ve changed the album title, and I can understand why, because you’ve got Joe Chiccarelli, who’s known for his work with White Stripes; he’s worked with you with Oxbow before and with Morrissey. You gave him the original analogue tapes, and it was more than just a remix job; he had to restore them as well?

“Oh man, it was a huge job! Part of how this happened is that I’ve left America. I no longer live in America, and as part of this, I was packing up all my shit to send. I had to go over to my ex-wife’s house and clean out all the shit that I still had there, and what did I find? I found one reel. One reel. So, we were just gonna remix a few of these songs. Then it was sounding so good that everybody said, “Well, it’s too bad we can’t do the whole record.” I go, “Jesus Christ, now I gotta find this other roll of two-inch tape.

I dug and I dug, and it was hard. I’ve lived in California since 1980. This is a lot of stuff to go through, and I finally found the second one. I thought it was great. I’m done. I could just send this off. Joe Chiccarelli was like, “Ah, this is an old tape. It lasts a long time, but if I put this in the machine right now, I have to rent the two-inch machine, and you’re just gonna leave all these deposits there. It’s not gonna work.” So, you have to send it to this lady. There’s like one lady in California who does it, and she’s got this special deal at her house. She has a special oven, and she bakes old recording tape, and apparently that causes it to congeal, and she charged us an ungodly amount of money. So, she baked these tapes. Then I took the tapes to the studio where Oxbow recorded the last bunch of records up in 25th street studios in Oakland, and then the guy digitised the big tapes, and then I had to send the digital stems to Chiccarelli. So, it was super involved, if you’ve got your master’s around, cool, but there are going to be a bunch of steps before you can just get that shit into Pro Tools.”

Is that why you decided to give it a new name? Because it’s gone through such a transformation?

“We didn’t decide to give it a new name until we heard it. Then we said, “No man, this sounds so great.” Muru Muru will forever be the name of the failed second Whipping Point record. But this thing that we’re thinking that will succeed because you can hear what we wanted to do, it deserved a new name, and Steve came up with a great one. Which is funny, since I’ve named every single Oxbow record, written all of the lyrics, that’s become kind of like my job, but Steve, true to form with Whipping Boy, he came up with the name Whipping Boy, and he came up with the name Dysillusion, which I liked. So, I was like, I’m glad to not have to do everything. So that’s amazing!”

I mean, it is radical even by today’s standards, you can hear stuff in there that is reminiscent of the preemptive curve that Fishbone might have taken, you know, and there’s obviously Minuteman, where funk started intermingling with Hardcore.

“It seemed really natural to us because every single one of those songs we played live. They were couched with all these other hardcore songs, but we played them live. So, it shouldn’t have been a complete and total surprise to everybody. But largely, it was what happened with that record that caused me, when I started Oxbow, for the first two records to have no credits, nothing. I didn’t want people to do that lazy thing of going, “Oh, this is just a guy from Whippin’ Boy’s new band. They went crazy, took too much acid.” Nah, forget it. I don’t want that. I want it to be judged on its merits. So, there were no credits for Fuckfest or for King of the Jews. I mean, I later put together a booklet that you could buy to go with it that had lyrics.

First two, I did not want it. I wanted it to be judged cleanly, and that’s another reason why we have altered the name. But yeah, there’s a lot of stuff, and if you look at the people who, like I said, we only sold to 175 people, but all those people you’ve named, I have not been surprised at all if they had heard the record. Because it was like Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate. It was so noteworthy as a colossal, ambitious failure that I think that people, or like the Bill Cosby movie I was in in 1987, the worst movie of 1987, Leonard Part VI. I actually made a lot of money on that because it was so bad that people went to see it. Just to see how bad it was.

In the instance of Dysillusion, it always seems strange to me that it seems strange to everybody else. But you know, maybe I’m just saying that because we were playing shows with The Minute Men, and we were playing shows with Husker Du, and we were hearing their next generation stuff live before anybody else heard it. I think we even played with the Meat Puppets once.

But we played with The Damned. We played a lot of shows with a lot of people. The bands that interested us the most were doing just exactly what we were doing. You know, SSD, one of my favourite hardcore bands, that record they did that kind of finished them, How We Rock, that people go, “oh, it’s essentially an ACDC cover record.” And I was like, exactly. That’s exactly what they wanted to do. That’s exactly what they did. You should appreciate it on its merits, but it destroyed the band. There were not a lot of second lives in Hardcore. I mean, you know, Discharge was doing great, and then they had some scandal, and that was it. You know, people were not dealing with you guys anymore. Stupid!”

Muru Muru was intensely personal, I was writing about my emotional life for the first time to a certain degree, and we got scared off of that.

Look at what happened with Black Flag’s fans when they put out My War. They were accusing them of turning into Black Sabbath.

Yeah, but see, when that happened, Henry was staying at my house, and he was telling me why they were growing their hair and the audience response, and it was so foreign to me what he was saying. I was like, “What are you fucking talking about? Don’t they understand?” That’s when I should have clued into the fact that if I put Muru Muru out the way I intended to put it out, the response was going to be colossally hostile. I just didn’t see it. And he was sitting on my couch, telling me that this is the kind of shit they would deal with. I was like, “Well, that’s you, our fans have bigger minds.” They’ll be able to understand what we meant, you know? But he was right.”

Would you say that this album was the creative catalyst for all your further experimentations with Oxbow and now Buñuel?

“Well, also you gotta understand, like this was the first time that I had written a lyric for a song that dealt with emotional issues, The Sound Of No Hands Clapping, you know, it was a bit of agit pop, you know, with America Must Die and Amnesiac. There are a couple of songs on there that you can draw a line from that to Oxbow and to Buñuel and all these later kinds of projects, but not many. And you know, Muru Muru was intensely personal; I was writing about my emotional life for the first time to a certain degree, and we got scared off of that. So, The Third Secret of Fatima is more traditional and doctrinaire. It’s not hardcore, but it’s more rock and roll. The songs are still personal. I was writing songs for the band. It’s very different. Oxbow was me writing for me, and Buñuel is me writing for me, and Muru Muru was the first exercise of me writing for me, and it was received so poorly. But like I said, Whipping Boy put out two more records after that. I didn’t do that shit again until I had to do Oxbow,

I had to do it, didn’t feel like I was going anywhere, like I’ve said many a time before, Fuckfest was supposed to be a suicide record as a suicide note, because I felt done. I felt done completely. Of course, it was received so well that my ego kept me alive. I mean, that’s what it was. That’s why it was weird to do the memoir, right? Like, I’ve done a bunch of books. A Long Slow Screw was a novel. I did the Fight book. If you don’t like those books, then, you know, Long Slow Screw, you don’t like crime fiction, you know? If you don’t like the Fight book, you know, you’re not interested in fighting. It’s just not your jam, you know. But the memoir was kind of a hard book to put out there because it’s like, if you don’t like this, you pretty much don’t like me. The fact that you bought it meant that you thought you liked me, and now that you’ve read the book, you realise that you don’t like me at all. It’s kind of hard. I’m a fucking hardcore punk rock guy at base root, so I’m completely comfortable with being hated by people. The memoir was a little bit different.

The goal was to actually tell the truth, whether or not it made me look good. I think I managed to do that. I think with Muru Muru, that’s what we want, to speak to a certain quality of truth, and we did, and it was poorly received. So, the next two records of Whipping Boy (Speaker 1) were really emotionally dissatisfying for me. When I said, OK, I’m going to do a record that I can just be me being me, and that’s the last thing I’m going to do before I exit this planet where nobody or nothing gives a fuck whether I live or die, that record became Fuckfest, right?

Finally, I saw that at the risk to my own soul, I must do me, at every given opportunity, because this other thing was bearing no fruit. It wasn’t making me happy, and it was achieving nothing. So, in other words, every record I put out after Muru Muru should have been like Muru Muru. Indeed, after the last two Whipping Boy records, that’s precisely what I’ve done.”

The more you go down this musical path, the more it goes back to the initial idea of three chords and the truth. It seems the truth is the most important thing.

“I said that, and a guy called me on that the other day. I go, what are you talking about? Because we started to talk about Lana Del Rey, and I go, “yeah, I can appreciate on one level, the songs and the music and stuff, but it still bothers me that it was constructed in the same way that it bothers me that I found out The Monkees were constructed.” He goes, “What do you care?” And I go, “I don’t know, I’m a bear for authenticity.” He goes, “If I walked in here right now and I had some portable music device and it was playing one of her songs, you would like it. How is it that when you find out this other stuff, you don’t like it?” I go, “because authenticity is part of how that fucking cake is baked.” You know, if you don’t care about authenticity, then you don’t care whether the cake is good or bad. You just in general, like cake, right? So, Lana del Rey is fine in general, the music is fine, but it would mean a lot more to me if she really meant it because that’s just part of how I like to embrace my art.”

Someone said to me the other day, there’s a big difference between good commerce and good music.

“Yeah, and there’s music out there that exists, completely disconnected from any need for authenticity. I used to be a disco dance instructor in the late 70s. There’s a lot of that music that is inauthentic as shit. But that’s not what I go to it for, man.”

Well, it’s knowingly being that isn’t it?

“Yeah, correct, and that five-year period from 70 75 to 80 was a very unusual period in American music as well. That’s where everything fractured from the creation of punk rock, but also disco, before disco destroyed itself, it got me. Everybody kind of came back, the Vietnam War ending, and then the war back home with all these damaged souls showing up, and you know, easy accessibility to drugs, and then there was no AIDS yet. So, fuck it was a strange, strange, strange time. But authenticity has always meant a lot to me.”

Now this part of history has been restored. Was it something that was niggling at you for the last 40 years that that album was unfinished business? Can you rest on this now?

“Yeah, I can, of course. Everybody who could claim to be interested or involved in Whipping Boy at all, they all have, they’re all like different people, right? They’re like the Human Farm, Sound No Hands Clapping crowd, there’s a very small Muru Muru crowd, and then there’s a Third Secret of Fatima crowd. And so, the people who really love Third Secret or Fatima are really wanting the same thing to happen to that record, but I will never do that to Third Secret, because it was close enough. Klaus had gotten better. We worked with this jerk-off that he had worked with before, but I absolutely didn’t like John Cunaberti, who had done a bunch of Dead Kennedys records, but I hated Cunaberti with a passion, and he apparently hated us as well.

But the Third Secret of Fatima sounds much better than Muru Muru did, but I have, with the exception of a song like Smokey, or Enemy, we had a couple of songs off of that that were salvageable, but I’ve never listened to that record again, like ever. Or the 7-inch that was the last kind of thing we put out before CDs, never listened to that anymore either. Muru Muru, I listened to. Now I can listen to the Chiccarelli version. So yeah, it’s the finished business, of course, now with this record out, a lot of people have said,” Oh my god, yeah, you guys were great, how about playing again?” And you know, the one guy who asked me this, of course, is a Sound of No Hands Clapping guy. So, he was like, “Yeah, man, I could get you booked.” I go, “Great $10,000.” That’s kind of steep for the band. I go, no, that’s for me. Get me to stand on stage and sing what you want me to sing, which is like America Must Die, or Speed Racer, or one of these other songs. It’s just that I can’t, man. No, I don’t want to do this.

I would play the songs off of Muru Muru again, and that’s when it gets sort of interesting. The band that played on that record is all very excited to have reissued this record, but it would just be too crazy. I can’t imagine that it would be emotionally or aesthetically pleasing at this point to go through the process of learning those songs again and playing them live. It would be better and best for me, but I can’t see that it would be useful for those other guys who’ve all gone on to greater and more interesting non-musical careers.

I found it interesting that Dave, who’s now an esteemed professor at Vanderbilt, won a big award. I think he’d done some work through the university with the Chicago Cubs or some shit. It was crazy, these guys are geniuses, and he got a bunch of cash from it, and I go, Ah, good for you, man. He goes. “First thing I did when I got the cash, I went and bought a new drum kit!” He’s been playing again. So, it’s like, if we could tour because we never toured on Muru Muru, right? Because it was like, fuck it, and that was the end of that. It killed that version of the band when it came back. The Third Secret of Fatima is a totally different band. I mean, Steve Ballinger plays bagpipes on Third Secret and doesn’t even play guitar. So, it’s not entirely a bad thought, but it’s super unlikely to happen.”

https://www.facebook.com/eugenerobinson

Interview By George Miller